By

Freedom C. Onuoha, University of Nigeria

and

Oluwole Ojewale, Institute for Security Studies

Africa’s biggest election will be held in February 2023 in Nigeria. It’s the seventh successive general election in the country’s 23 years of unbroken democratic government.

The election will be a massive operation. An estimated 95 million registered voters will go to the polls in 176,846 polling units across 774 local government areas.

A total of 12,163 candidates sponsored by 18 political parties are on the ballot. They are up for election into 109 senatorial districts, 360 federal constituencies, 993 state constituencies, 28 governorship positions, and the office of the president.

But there are rising fears that security crises in the country could undermine the outcome. Nigeria’s security apparatuses seem unable to guarantee safety.

We think there are indeed grounds for concern. Based on our expertise and previous work on violence in Nigeria, we believe that potent threats to a free, fair and credible election could come from both physical and virtual spaces.

In the physical environment the threat comes from Boko Haram terrorists, bandits, separatists, criminals, militants, armed herdsmen and a host of violent gangs.

In the virtual space, it comes from hacking, misinformation, disinformation, deepfakes and fake news.

Election security is a defining factor of Nigeria’s electoral process. Past elections have been characterised by brazen acts of violence largely perpetrated by political thugs. But the speed, spread and scale with which violence has evolved make the 2023 elections particularly concerning.

Recent instances of violence show that the country is in a different and more dangerous security environment. In recent months armed groups have killed or abducted citizens. There have also been targeted attacks on the facilities and security agents connected to the Independent National Electoral Commission. And an unprecedented number of communities are under the partial control of non-state armed groups.

Some desperate politicians, too, may encourage armed groups to cause violence in opposition strongholds as a way of suppressing voter participation.

Deteriorating security situation

Over the past months, attacks in Nigeria in the physical and virtual domains have increased significantly. At least 7,222 Nigerians were killed and 3,823 abducted as a result of 2,840 violent incidents between January and July 2022.

Cybersecurity has also deteriorated. Data released in May 2022 showed that Nigeria was one of the worst hit countries in Africa in terms of cyber-attacks. South Africa was the most targeted with 32 million attacks. Nigeria had 16.7 million cyber-attacks.

This is pivotal as the Independent National Electoral Commission plans to use the Bimodal Voter Accreditation System for the upcoming poll. This system and an Election Result Viewing Portal are two technological innovations celebrated for improving the transparency of election results and boosting public trust in the outcomes.

With this in mind, the Independent National Electoral Commission has repeatedly expressed concern over prevailing security challenges ahead of the 2023 elections.

Armed groups and the 2023 elections

The actions of armed groups are already affecting core elements of election security.

Since 2017, there have been nine abductions involving electoral commission staff, 20 attacks on election facilities, and 17 incidents of looting and property destruction. Offices and sensitive equipment have been targeted.

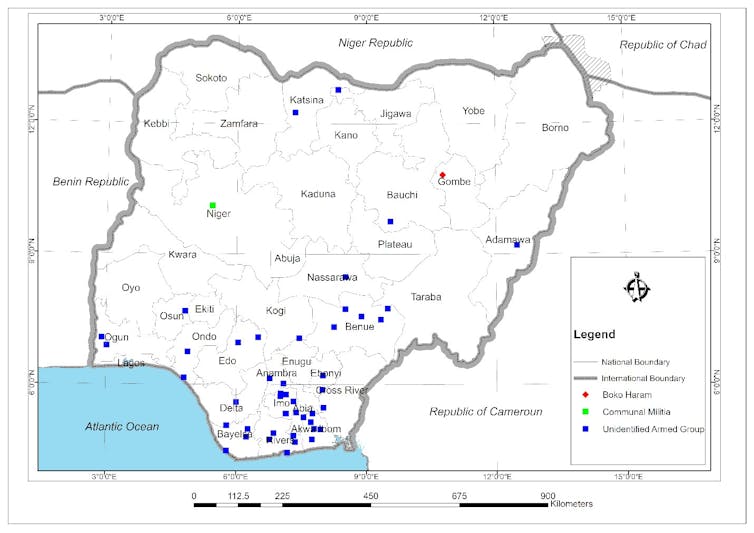

The attacks have been concentrated in the south, especially the south-east. (See figure 1).

Since the 2019 election unidentified armed groups have attacked commission offices.

For instance, on 26 November 2020, Boko Haram members attacked the electoral commission office at Hawul local government in Borno State.

In April 2022, unknown gunmen shot dead a commission official at a voter registration centre in Ihitte Uboma local government area of Imo State. The electoral commission suspended voter registration exercises across 54 centres and in three local government areas in the state.

These attacks portend serious danger to national electoral activities.

Attacks targeting infrastructure could scare away prospective voters, cause significant shortages of electoral officials, compromise logistics, and endanger the supply of electoral materials.

Security forces have also borne the brunt of attacks and killings. For instance, 81 soldiers, 65 police officers, two correctional service officials, two anti-drug law officers, five officers of the civil defence corps and two road safety officials were killed by non-state armed groups between January and June 2022.

The killings were mostly carried out in the north-west, north-central and south-east regions.

Security agents are critical to providing a safe environment during the entire electoral process.

Security response plan

The government needs put in place a robust and comprehensive security plan to deal with the risks to a smooth election process.

Security forces must plan for operations involving, for example, ground and air raids against armed groups in their strongholds. There also need for information and psychological operations to tackle the propaganda and disinformation put out by armed groups.

A robust information operation response should be both proactive and reactive. This will help build voter confidence and reduce the appeal or threats of armed groups.

The Department of State Services, in partnership with the Office of the National Security Adviser, should lead and coordinate this response.

Finally, protecting the forthcoming election requires a whole-of-society approach. It also requires the election management body and the nation’s security apparatuses to work closely together.

The country’s inter-agency consultative committee on election security offers a great platform for this to happen.

Freedom C. Onuoha, Senior Lecturer, Political Science , University of Nigeria and Oluwole Ojewale, Regional Coordinator, Institute for Security Studies

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.